Spatial Flight Control, how true 3D flight control is redefining industrial drone systems

Visualization: © Ulrich Buckenlei | Concept illustration of spatial flight control for autonomous systems | Editorial representation without claim to technical accuracy

Autonomous drone systems have evolved rapidly, yet a core principle has largely remained the same. Most multicopters move horizontally by tilting their entire body. This approach is efficient and robust, but it tightly couples orientation and movement, causing precision and interaction to quickly reach their limits in complex environments. In industrial scenarios where proximity to infrastructure, confined spaces, turbulence, and safety critical processes converge, this coupling becomes the limiting factor.[1][2]

Spatial Flight Control describes the transition from planar flight logic to true spatial control. It refers to a control approach in which translation and orientation no longer have to occur together, but are regulated as separate variables. Space is no longer treated as a surface, but as a volume in which position, direction, rotation, and working distance remain simultaneously and stably controllable. What may initially sound like a niche research topic is in reality a new control paradigm with direct implications for industrial automation, safety architecture, and system design.[1][3]

The visualization deliberately condenses this shift into a conceptual image. It does not depict a concrete product, but an idea: flight robots that can maintain a stable spatial trajectory while actively changing their orientation. The focus is not on mechanical accuracy, but on the underlying control logic, meaning the question of how a system distributes forces and torques in such a way that spatial control remains reliable even under dynamic orientation changes.[2][3]

Why classic flight logic reaches its limits

Conventional multicopters generate horizontal movement through tilt. This keeps flight generally stable, but orientation and trajectory are physically coupled. As soon as the system rolls or pitches, the thrust vector automatically tilts, and the movement path changes. For simple missions, this is efficient. For precise work in confined, dynamic, or safety critical environments, however, it creates a structural problem: every correction simultaneously changes attitude, viewing direction, distance to the environment, and the resulting trajectory.[3][4]

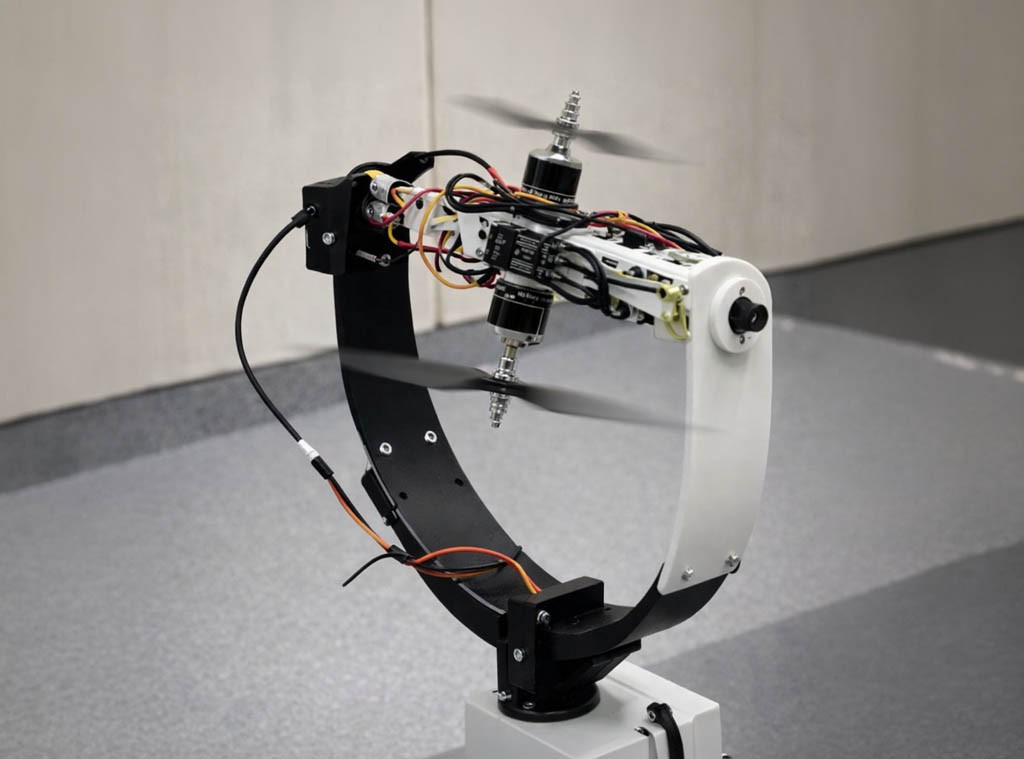

The new motor concept shown in the image makes this bottleneck visible. Instead of rigid propeller axes, the system uses two counter rotating rotors per drive unit and an active mounting with up to 160° of articulation. This allows the thrust vector to be aligned deliberately without tilting the entire drone body in the same direction. The platform remains aerodynamically calmer, while the drives perform the directional work. Translation is no longer derived from tilt, but from actively set thrust direction.[1][3]

In industrial facilities, the benefit becomes immediate. Anyone working close to pipes, beams, machines, or cables needs reproducible movements and stable safety distances. In classic logic, these requirements are often solved through conservative flight profiles, larger radii, or additional infrastructure. With swiveling, dual mounted drive units, space can be controlled more sensitively, because micro corrections occur at the motors, not through global tilting of the entire airframe. This reduces drift, enables more precise approaches, and stabilizes interaction in tight spaces.[1][4]

Dual rotor and 160° joint: the thrust vector is actively aligned, orientation and trajectory are decoupled

Visualization: © Ulrich Buckenlei | Concept illustration | Editorial representation

The decisive point is not speed, but control. As long as orientation and translation remain coupled, space is not freely controllable, but a byproduct of attitude. Swiveling dual rotor drives shift the logic: space becomes the primary control objective, while body posture becomes secondary. This is exactly where the transition from classic multicopter logic to Spatial Flight Control begins.[1][3]

- Coupled motion → tilt generates translation and changes the thrust vector

- Active vectoring → dual rotor plus 160° joint aligns thrust independently of the body

- More precision in tight spaces → corrections happen at the drives, not through global tilting

These three points mark not only technical differences, but a structural break in flight logic. While classic multicopters enforce stability by keeping attitude changes as small as possible, stability here emerges through continuous, finely resolved regulation of the thrust vectors. The system treats motion as a normal state and compensates locally at the drives instead of globally at the entire body.

Especially in industrial scenarios, this difference becomes decisive. When drones operate along lines, in shafts, between beams, or close to sensitive infrastructure, it is not enough to “fly calmly.” What matters is the ability to control distances, viewing directions, and contact zones independently. Spatial freedom does not come from stillness, but from controlled, decoupled motion.

This also changes the role of flight control. It no longer primarily optimizes attitude and angles, but spatial states, distances, and relations. Orientation becomes secondary, space primary. This is where the transition from classic multicopter logic to Spatial Flight Control begins. Not as an additional feature, but as a new paradigm of flight control.[1][3]

The next chapter shows what spatial flight control means technically, and why it is less an extension of existing systems than a new class of control architectures.

Spatial Flight Control – space becomes a controllable volume

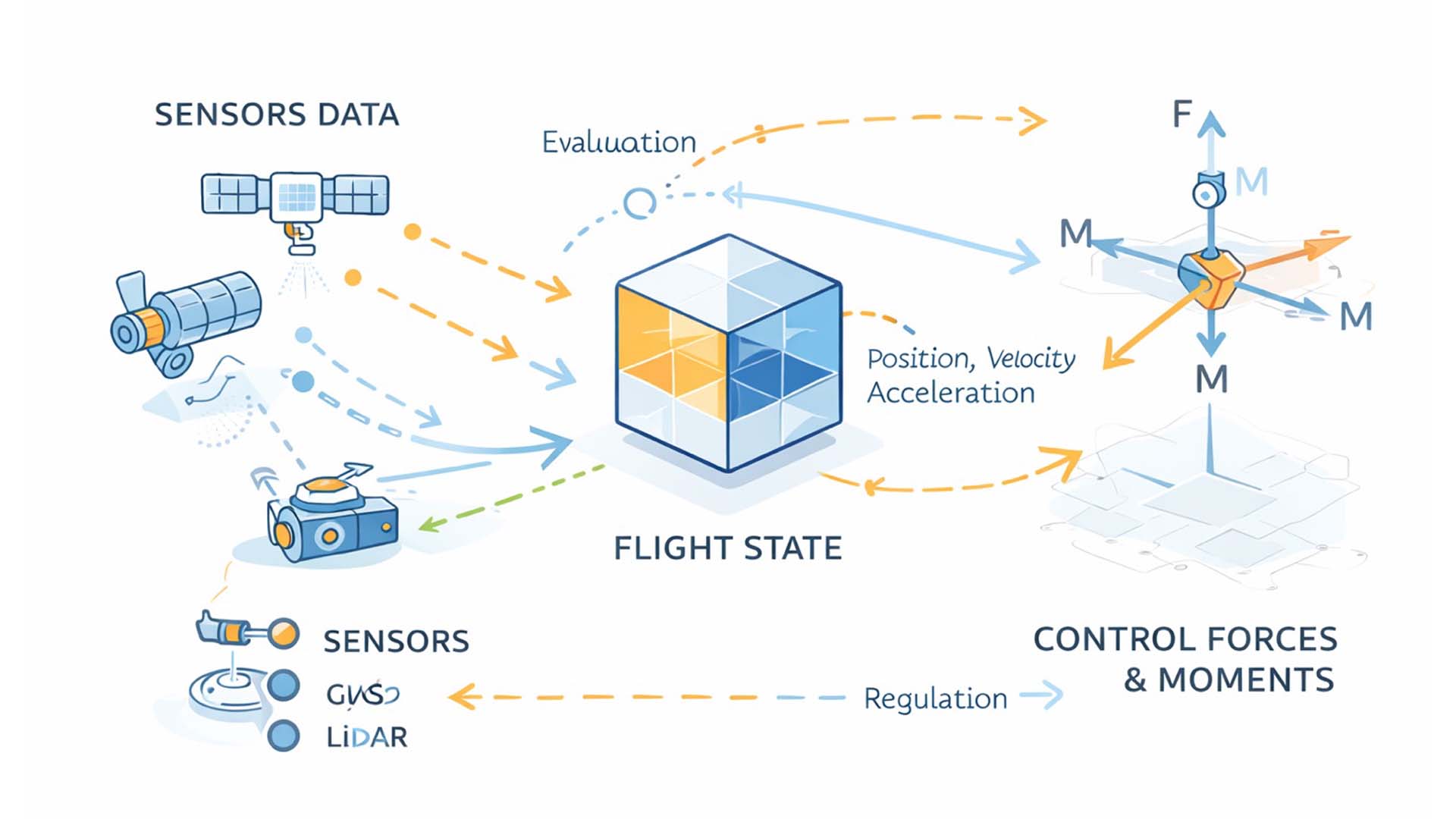

Spatial Flight Control describes a control approach in which space itself becomes the primary control object. The flight robot continuously captures its full three dimensional state and treats position, velocity, acceleration, as well as rotational quantities such as roll, pitch, and yaw no longer as dependent chains, but as equally ranked control variables. The decisive point is not to maintain a specific attitude, but to keep defined spatial states stable, regardless of how the platform is oriented in the process.[1][5]

This fundamentally changes the understanding of flight. Movement no longer arises from a sequence of attitude changes, but from the direct regulation of spatial coordinates. Orientation becomes a freely selectable variable within clearly defined limits, while the motion vector is actively and continuously controlled. The flight robot no longer follows implicit aerodynamic constraints, but explicit spatial target variables.[1][5]

This principle is intentionally presented in an abstract form in the visualization. Instead of a concrete aircraft, the image shows the control space itself: state variables, feedback loops, and corrections are visualized as interconnected layers. Forces, orientation, and motion do not appear as mechanical effects, but as controllable parameters within a continuous control loop. Space is not described by geometry here, but by states and transitions.[5]

Spatial regulation: orientation and translation are controlled as separate variables

Visualization: © Ulrich Buckenlei | Concept illustration | Editorial representation

Stability in this model does not emerge from avoiding deviations, but from actively compensating for them. The system permits rotation, acceleration, and local disturbances, but responds immediately through targeted adjustment of force and torque distribution. Stability is no longer a static target state, but a dynamic equilibrium that is continuously recalculated and adapted.[1][5]

This form of control places high demands on the underlying system architecture. Sensing, state estimation, and control algorithms must work in tight integration. Inertial sensors provide high frequency motion data, visual odometry and LiDAR capture relative spatial structures, while GNSS RTK provides global references. Only through real time fusion of these data does a consistent state space emerge in which spatial control becomes reliably possible.[5][6]

- Decoupling → orientation does not automatically determine the motion vector

- Continuous compensation → stability emerges through permanent feedback

- Volumetric navigation → space is understood as a controllable volume

These points represent more than a technical improvement. They stand for a shift in perspective: flight is no longer interpreted as movement along a line, but as controlled presence within a defined spatial range. The robot does not “hold” a point target, but remains within a volume described by distances, tolerances, and process boundaries. In doing so, flight control approaches the logic of industrial motion control known from robotics and automation.[1][5]

For industrial applications in particular, this transition is decisive. Processes require repeatability, predictability, and clear state models. Spatial Flight Control creates the basis to treat flight robots not as moving sensor platforms, but as spatially operating systems that can be precisely integrated into existing workflows. Flight becomes part of a controlled process, not an improvised maneuver.[1][5]

Innovation potential, precise work instead of spectacular maneuvers

The industrial value of Spatial Flight Control does not lie in the visual effect of individual flight maneuvers, but in the ability to define space as a stable working area and to maintain it reliably. While classic drone systems primarily understand movement as a sequence of attitudes and transitions, the depicted control logic shows a different approach. The platform remains within a clearly bounded volume, while orientation, rotation, and local compensation movements are actively permitted. Flight is interpreted not as a dynamic performance, but as a controlled state.[2][4]

The illustration makes this difference clear. The dashed spatial volume does not describe an idealized path, but a permissible working area. Within this volume, the platform can move, rotate, and compensate without leaving the defined spatial state. The drawn motion paths show that corrections do not occur via global attitude change, but via local adjustment of the drives. Rotation is not avoided, but used deliberately as long as position, distance, and process boundaries remain satisfied.[2][4]

This creates a decisive advantage especially in inspection, surveying, or monitoring tasks. Sensors and cameras no longer need to be aligned through a forced flight attitude. Instead, the platform can flexibly adjust its orientation while keeping the spatial position stable. Distances to facilities, components, or structures can be kept constant even under turbulence, thermal effects, or external disturbances. Control intervenes where deviations arise, not where they become visible.[2][6]

Industrial precision: stable spatial positioning even with active attitude changes

Visualization: © Ulrich Buckenlei | Concept illustration | Editorial representation

The key shift is how such systems are evaluated. The quality of a flight robot is no longer measured by range, maximum speed, or spectacular maneuvers, but by the reliability with which defined spatial states are maintained. The spatial volume shown in the image becomes the actual reference variable. As long as the system moves within these boundaries, the process remains stable regardless of momentary attitude or rotation.[1][2]

- Precision work → stable spatial positioning within defined volumes

- Confined environments → navigation without the need for permanent attitude correction

- Process integration → flight becomes a controlled work step

These properties mark not an incremental improvement, but a functional shift. Flight robots evolve from mobile sensor carriers into spatially operating systems that actively maintain states, distances, and tolerances. The logic increasingly resembles industrial automation: clearly defined workspaces, permissible deviations, and continuous control instead of occasional correction. Spatial Flight Control thus forms the foundation to establish flight as a reliable industrial capability, not an exceptional operating mode.

The next chapter focuses on how this form of spatial control is translated into autonomous operational logic. Not as a single maneuver, but as a systemic capability that works continuously, independently, and reliably.

From maneuver to system logic, autonomy as controlled self regulation

Once spatial flight control is reliably mastered, the focus shifts fundamentally. The single maneuver is no longer central. Instead, the system logic that evaluates states, sets priorities, and derives consistent behavior takes the lead. What matters is not whether a flight robot can technically perform a movement, but whether it continuously understands the state it is in, which options are permissible, and what consequences its actions have. Autonomy in this context does not mean freedom without constraints, but controlled self regulation within clearly defined rules, boundaries, and responsibilities. The system acts independently, but not without limits.[2][7]

At the core of this architecture is continuous state evaluation. The flight robot permanently captures sensor information, energy state, spatial position, velocity, distances to objects, mission progress, and internal system parameters. These data are not processed in isolation, but merged into a shared state space. Only this consolidated view enables decisions that are not merely reactive, but context aware. Behavior does not arise from rigid flow plans, but from the continuous evaluation of this state space and the selection of suitable actions within defined constraints.[2][7]

In Spatial Flight Control, this system logic becomes especially important. Decoupling orientation and translation greatly expands the action space, but also increases the complexity of state monitoring. The system must not only know where it is, but also how stable that state is, which energy and control reserves are available, and which deviations remain tolerable. Autonomy here does not emerge from maximum freedom of motion, but from the ability to constrain degrees of freedom depending on the situation and to use them responsibly.[7][8]

Systemic autonomy: state estimation, mission logic, and feedback as a continuous control loop

Visualization: © Ulrich Buckenlei | Concept illustration | Editorial representation

The illustration depicts this logic as a closed loop. Sensing, state model, mission context, and decision logic are not connected linearly, but remain in constant feedback. Energy availability, environmental conditions, and safety boundaries continuously feed into evaluation and shape the system behavior in real time. Decisions are not made once, but continuously reviewed, adjusted, or revoked. Return strategies, safe waiting positions, performance reduction, or mission abort are integral parts of autonomy, not safety mechanisms added later.[7][8]

For industrial applications, this architecture is decisive. Scaling does not come from removing control, but from formalizing it. An autonomous system must remain explainable, respond predictably, and provide defined points of intervention. Spatial Flight Control is therefore less a single algorithm than an architectural decision about how responsibility is embedded in the system between control, decision logic, and human oversight. Autonomy becomes a prerequisite for industrial integration, not a risk.[2][7]

- Systemic autonomy → behavior emerges from continuous state evaluation

- Energy as a control variable → mission scope and return are dynamically adjusted

- Degradation logic → controlled transitions instead of abrupt loss of control

This form of autonomy is not a radical break, but a logical evolution. Flight robots do not become independent actors, but reliable technical systems that operate autonomously within defined frameworks. Autonomy thus becomes the basis for industrial usability. It makes flight planable, integrable, and controllable.

The next chapter addresses how this systemic autonomy remains connected to human responsibility, meaning how Human in the Loop is understood not as an emergency workaround, but as an integral part of controlled autonomy.

Human in the Loop, control remains with the human

As autonomy increases, the role of the human changes fundamentally. Direct control becomes the exception, while oversight, approval, and responsibility move to the forefront. This is not a loss of control, but a prerequisite for scaling. In industrial environments, it is crucial that decisions remain traceable, that intervention points are clearly defined, and that responsibility does not disappear into an opaque black box. Human in the Loop means the machine handles real time control and physical execution, while the human sets conditions, monitors system states, and intervenes in boundary cases.[8][9]

This separation of operational execution and strategic control is central to industrial deployment of autonomous systems. The human no longer acts as a permanent pilot, but as the responsible instance at the system level. Mission parameters, safety boundaries, priorities, and abort criteria are defined by the human. Autonomy delivers its full benefit only when human interventions are not constantly necessary, but always possible. Control is not abandoned, but abstracted and formalized.[8][9]

For Spatial Flight Control, this principle is especially relevant. Decoupling orientation and translation increases freedom of motion and expands the system action space. At the same time, new safety relevant states arise that are no longer covered by classic flight logic alone. Operational safety therefore does not emerge from restricting autonomy, but from transparent system states, clearly defined escalation logic, and regulated transitions between autonomous behavior and human decision authority. This structure determines in practice whether a system is perceived as a demonstrator or as an industrially robust solution.[8][9]

Human in the Loop: autonomous execution with clear control points and intervention options

Visualization: © Ulrich Buckenlei | Concept illustration | Editorial representation

The illustration shows how Human in the Loop works in practice as a continuous feedback loop. On the left is the human instance as an oversight point, not as a joystick pilot, but as a decision level. On the right, the system acts as the executing unit that captures states, evaluates risks, and suggests or executes actions. Between them are clearly visible loops that show information flows back continuously and not only in case of a disturbance. This continuous transparency is the foundation for operational trust.[8]

It is important that interventions occur at defined control points. Instead of interfering arbitrarily in control loops, the human works with approvals, priority changes, and clear stop conditions. In the graphic, this is hinted at by decision nodes and safety markers positioned between oversight and execution. This creates a system that acts independently, but can always switch into a safe mode when thresholds are exceeded or context conditions change.[8][9]

From the perspective of industrial decision makers, Human in the Loop is not a regulatory add on, but a deliberate design principle. It creates auditability, reduces operational risk, and makes autonomy organizationally compatible. Systems that do not communicate their states in an understandable way or whose intervention points are unclear are difficult to scale. Human in the Loop ensures that autonomy is not perceived as loss of control, but as a structured extension of human capability.[8][9]

- Oversight instead of presence → control from a safe distance and at system level

- Escalation logic → defined interventions in boundary cases and deviations

- Traceability → system states and decisions remain auditable

This form of human system interaction is not a contradiction between automation and responsibility, but their deliberate connection. Autonomous flight robots do not become uncontrolled actors, but cooperative systems within clear responsibilities. Human in the Loop makes autonomy socially, regulatorily, and industrially viable.

The next chapter shifts the focus to safety as architecture. Moving away from retrofitting individual functions and toward built in safety mechanisms that structurally secure autonomy from the start.

Safety as system architecture, not as a retrofitted measure

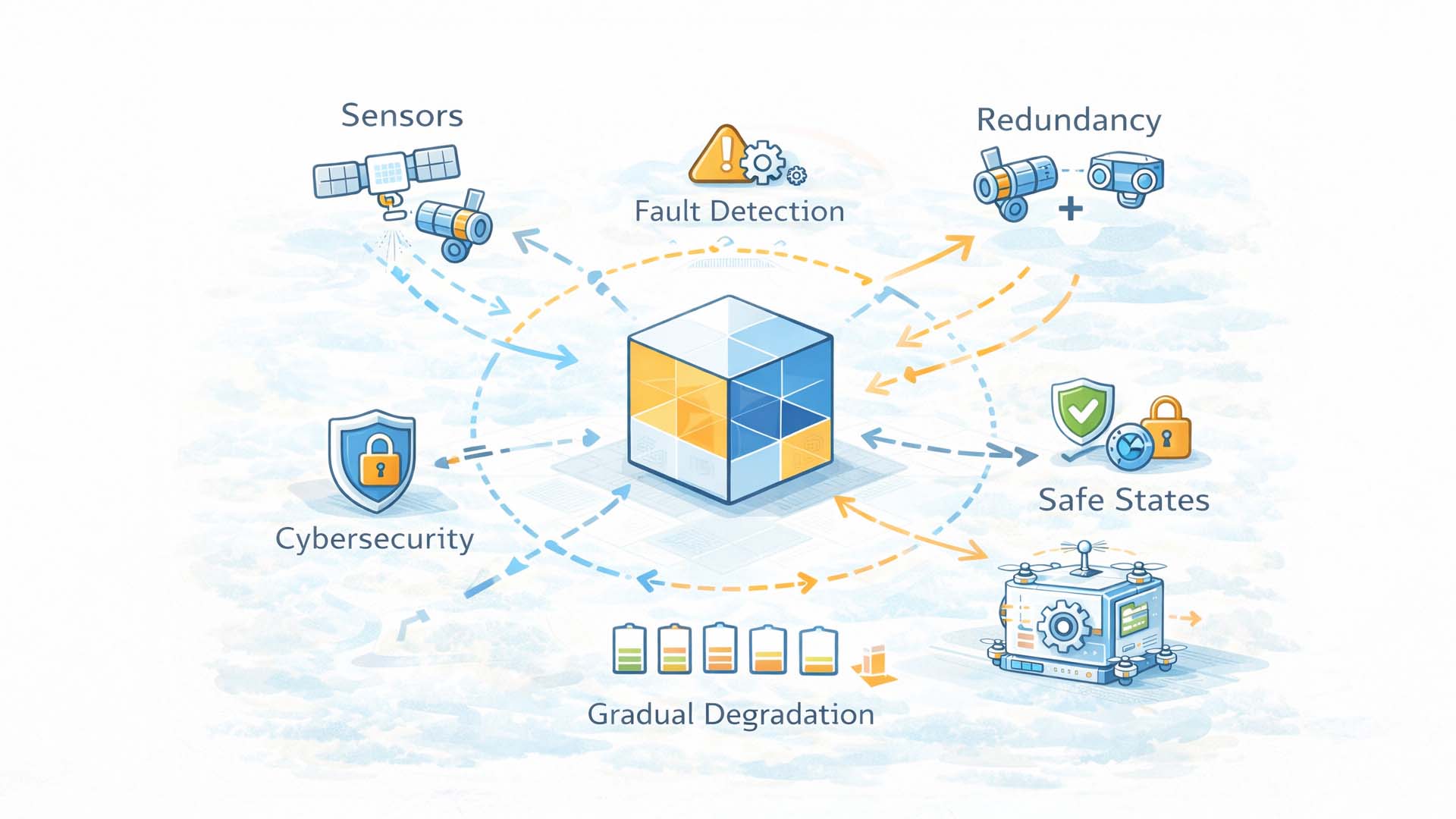

Spatial flight control changes not only movement logic, but also fundamentally shifts safety requirements. Not because Spatial Flight Control is inherently riskier than classic flight logic, but because it opens more degrees of freedom and therefore more possible system states. In this context, safety cannot be understood as an additional protective function or a retrofitted emergency shutdown. It must be embedded from the beginning as an architectural principle in the system. Permanent state evaluation, multilayer redundancy, transparent decision logic, and controlled degradation paths together form the foundation for trust in autonomous spatial systems.[8][9]

The core idea is a shift from reactive to preventive safety. Instead of reacting only to malfunction, the system continuously evaluates whether the current flight state remains within a permissible and stable state space. Sensor inputs from different sources are fused, validated, and consolidated into a consistent state core. Safety does not come from stillness or rigid limitation, but from the ability to allow motion in a controlled way, evaluate its quality, and restrict it deliberately when needed.[8][9]

A key difference compared to classic flight platforms is that stability is no longer tied to a specific attitude or orientation. Since orientation and translation are decoupled, safety must operate at a higher level of abstraction. The system evaluates not only position and velocity, but also uncertainties, reserves, redundancy states, and external influences. Safety thus becomes a continuous property of the system and not a binary state between “normal” and “emergency.”[8][9]

In industrial operation, two criteria come into particular focus: predictability and verifiability. A system must be able to explain at any time why it made a certain decision, which alternatives were rejected, and how that decision affects the future system state. This includes not only aerodynamic and control aspects, but also cybersecurity, communication outages, sensor faults, energy shortages, and mechanical deviations. The relevant question is therefore not whether a system can fly spectacularly, but whether it behaves in a controlled, stable, and compliant way under realistic disturbances.[8][10]

Spatial Flight Control in particular requires a safety architecture that evaluates states not in a binary manner, but on a gradient. Instead of “safe” or “unsafe,” there are graded operating modes. The system can reduce performance, restrict degrees of freedom, activate redundancies, increase distances, or transition into defined safe states. Degradation becomes a designed, traceable process rather than an abrupt loss of control. This capability is decisive for industrial acceptance because it makes failures planable, analyzable, and manageable.[8][10]

Safety architecture: state analysis, redundancy, and degradation logic as an integral design principle

Illustration: conceptual representation | Editorial visualization

The illustration makes this logic tangible. At the center is a consolidated state space that bundles all relevant system information. Around it are sensing, redundancy mechanisms, fault detection, safe operating states, and gradual degradation paths. Arrows and feedback loops show that safety is not a linear sequence, but a permanent control loop. Individual failures do not immediately lead to loss of control, but are absorbed through alternative data sources, reduced degrees of freedom, or more conservative decision logic.[8][9]

For decision makers, this means a clear shift in perspective. The assessment of flight robotics moves away from isolated hardware characteristics such as payload, range, or motor power and toward architectural questions. What becomes relevant is how risks are addressed systemically, how transparently states are communicated, and how well the system integrates into existing safety, compliance, and certification structures. Spatial Flight Control thus becomes an independent technology category, not because of a single component, but because of how safety is conceived as an integral part of the overall system.[1][5]

- Design based safety → risks are evaluated continuously and systemically

- Transparency → states, decisions, and transitions remain traceable

- Regulatory compatibility → architecture aligns with established safety and standards frameworks

Safety therefore does not become the limiting factor of autonomy, but its prerequisite. Only systems that structurally control their risks can be scaled, certified, and reliably integrated into industrial processes. Spatial Flight Control shows that expanded freedom of motion and high safety requirements are not a contradiction, but mutually dependent, when implemented cleanly as architecture from the start.

The next section presents the topic in motion and explains why controlled spatial logic is more relevant for industrial applications than pure flight acrobatics.

Video, spatial flight logic under real conditions

The following video shows flight behavior that would not be plausible with classic tilt based logic. The focus is on decoupled spatial control, meaning the system can keep its trajectory stable while dynamically changing its orientation. This ability is the core of Spatial Flight Control, not as a trick, but as an indicator of a new category of control and system design.

The sequences make visible what remains abstract in the text. A stable spatial position despite rotation is only possible if the system continuously estimates its full three dimensional state and balances forces and torques in real time. For decision makers, this matters because the real innovation is not in hardware aesthetics, but in the control logic that enables entirely new process forms in the first place.[1][5]

Video still as editorial context, rights remain with the respective rights holders

Video material from publicly accessible sources | Editorial analysis and context: Ulrich Buckenlei

Note: The video is embedded for journalistic and analytical purposes and optimized for mobile playback including iOS.

Sources and references

- IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, research on fully actuated multirotor systems, tilt rotor concepts, and control methods for decoupled translation and orientation. [1]

- Science Robotics, survey work on the limits of classic multicopter logic in complex environments and on new control paradigms in aerial robotics. [2]

- ICRA Proceedings, contributions on state estimation, sensor fusion, and real time control for aggressive and precise flight maneuvers under real disturbances. [3]

- IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine, industrial applications of aerial robotics in confined spaces, including safety aspects and process integration. [4]

- ETH Zurich, robotics research, publications on real time state estimation, control, and aerial manipulation as a foundation for spatial control. [5]

- PX4 Autopilot documentation, system architecture, state estimation pipeline, control loops, safety modes, and fail safe logic as a practical reference for industrial development. [6]

- EASA, fundamentals on Human in the Loop and operating models for UAS operations in the civil context. [7]

- EASA, Specific Operations Risk Assessment SORA, methodology for risk classification and mitigation logic for drone operations. [8]

- ISO, standards family on requirements for safe UAS operations and safety critical operating procedures. [9]

- ENISA and national guidelines, recommendations on cybersecurity risks and protective measures in the context of unmanned systems and critical infrastructure. [10]

When spatial autonomy becomes a decision question

Spatial Flight Control is not a short term trend, but a structural step in development. What matters is not the individual drone, but the control paradigm. Motion is no longer derived from stability, but from continuous spatial regulation. For technology minded decision makers, this shifts the evaluation basis: less focus on individual hardware characteristics, more focus on system architecture, process integration, and risk control.

Whether inspection, approach, operation in confined spaces, or preparation for interaction, spatial autonomy opens new action spaces, but also raises requirements for system understanding, safety design, and integration. The central question is therefore not whether this technology is relevant, but where it can be applied meaningfully, and which evidence is required in operation.

The Visoric expert team: Ulrich Buckenlei and Nataliya Daniltseva discussing autonomous systems, industrial AI, and the translation of complex technologies into understandable models

Source: VISORIC GmbH | Munich

This is exactly where the Visoric expert team in Munich works. The focus is on analytical classification of complex technologies, translating technical systems into understandable models, and supporting well founded decisions independent of manufacturers, products, or short lived hype.

- Classification of Spatial Flight Control: maturity level, opportunities, limitations

- Assessment of safety architecture, operational logic, and risk

- Translation of complex control systems for decision makers and stakeholders

- Concept development for visualizations, simulations, and explanatory formats

If you want to assess what role spatial autonomy and new flight control approaches can play in your industrial context, a conversation with the Visoric expert team offers a well founded, independent, and practice oriented perspective.

Contact Persons:

Ulrich Buckenlei (Creative Director)

Mobile: +49 152 53532871

Email: ulrich.buckenlei@visoric.com

Nataliya Daniltseva (Project Manager)

Mobile: +49 176 72805705

Email: nataliya.daniltseva@visoric.com

Address:

VISORIC GmbH

Bayerstraße 13

D-80335 Munich