Autonomous AI Laboratories: How GPT-5 and Robotics Are Restructuring Experimental Biology

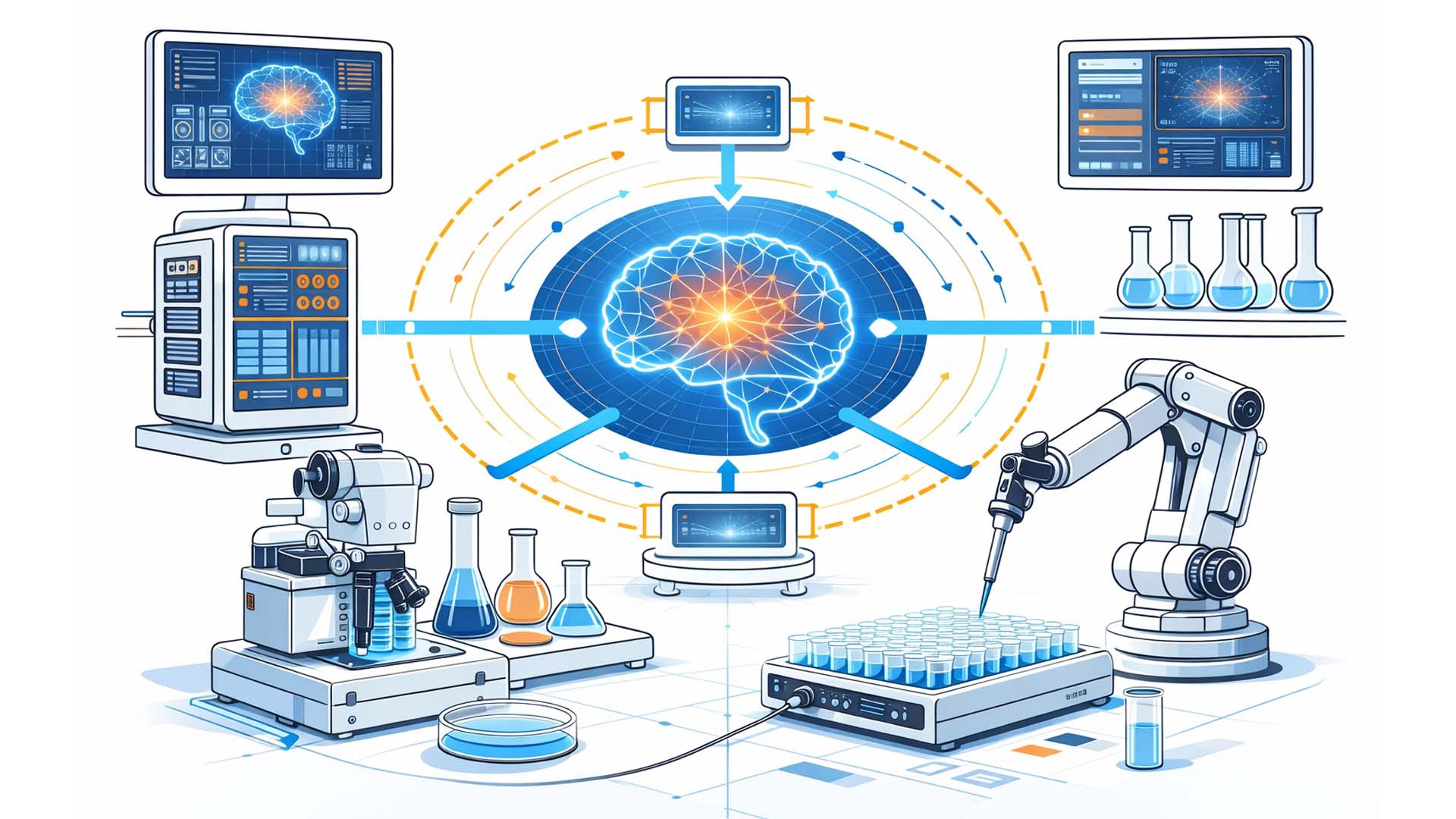

Visualization: Conceptual depiction of an AI-controlled closed-loop laboratory system | Editorial illustration without claim to technical precision

The recent collaboration between OpenAI and Ginkgo Bioworks marks a structural turning point in experimental research. For the first time, it was publicly demonstrated how a next-generation large language model independently plans, executes, evaluates, and iteratively optimizes real biological experiments. In this process, the model did not function merely as an analytical tool, but as an operational component of a closed laboratory control loop.[1][2]

At the center of the demonstration was the optimization of cell-free protein synthesis using GFP as a test system. Over six iteration cycles, more than 36,000 experimental variants were automatically executed. The result was a reduction in specific production costs of around 40 percent, from approximately 698 US dollars per gram to roughly 422 US dollars.[1][3]

What matters less than the absolute numbers is the structure of the process. The language model independently generated new reagent mixtures, validated them against defined laboratory rules, executed them via a modular robotic infrastructure, and subsequently analyzed the resulting measurement data. Hypothesis, execution, and evaluation thus formed, for the first time, a fully integrated AI robotics loop.[2][4]

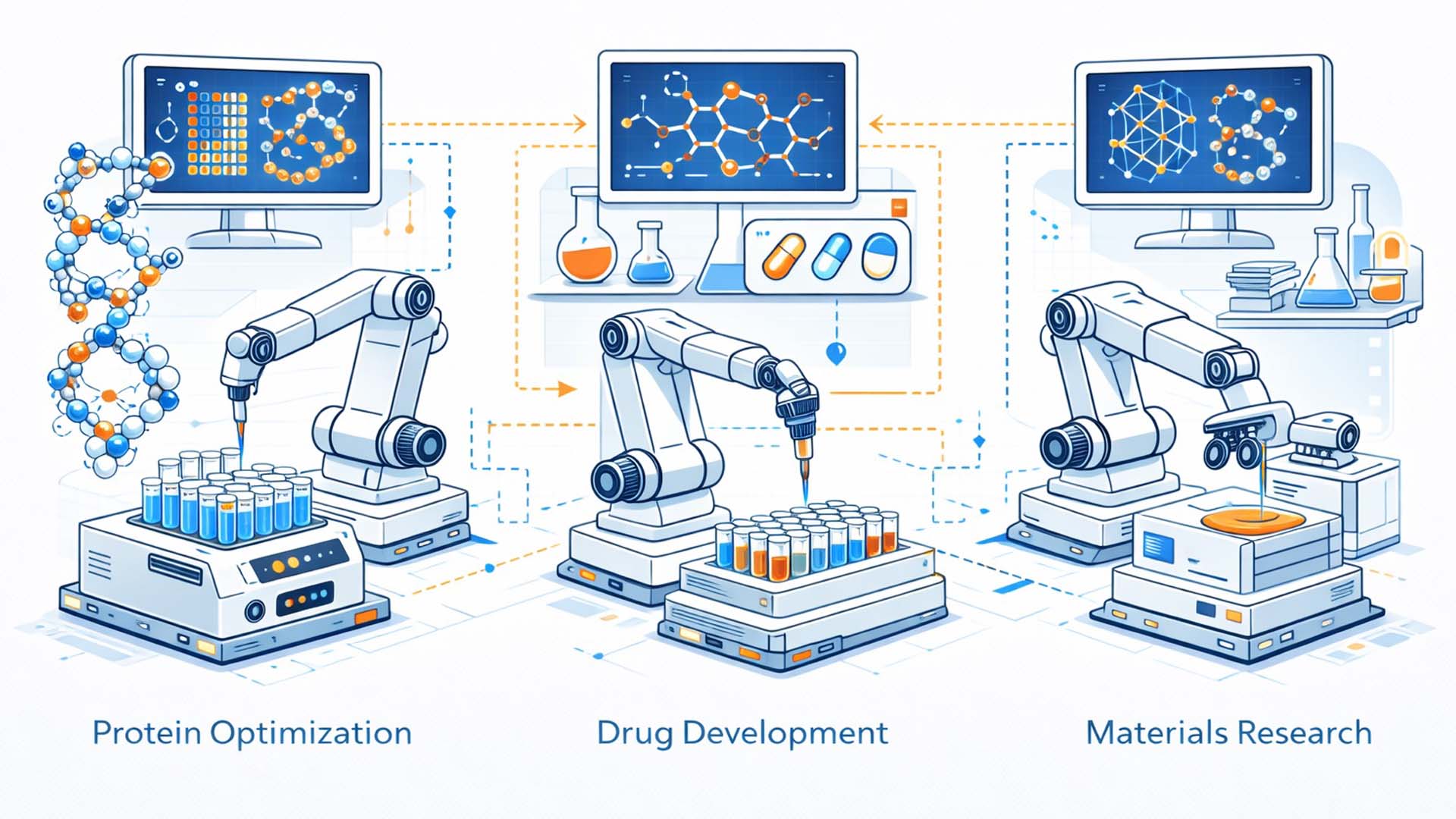

The visualization deliberately condenses this paradigm shift into a conceptual image. It does not depict a single device, but an architecture: a model communicating with laboratory automation via digital interfaces, triggering physical processes, and transforming their results into new decision logic in real time. Research is not only accelerated, but structurally reorganized.

Demonstration of the Autonomous Closed-Loop Laboratory

The demonstration presented in February 2026 was based on a closed experimental cycle. GPT-5 was granted access to a controlled computing environment with internet connectivity, scientific literature, and Python-based analysis tools. Based on historical data, current preprints, and experimental feedback, the model designed new 384-well plate layouts for cell-free protein synthesis.[5][6]

In total, more than 580 microplates were processed, generating nearly 150,000 data points. Each iteration consisted of generating new mixing ratios, robotic execution within Ginkgo’s cloud laboratory infrastructure, and subsequent measurement of protein expression using fluorescence detection.[1][7]

The physical implementation was carried out through so-called Reconfigurable Automation Carts, RACs. These modular units combine pipetting robots, incubation modules, and plate readers, which are automatically connected via conveyor systems. This creates a continuous laboratory workflow without manual intervention.[4][8]

Between the model and the laboratory hardware, a validation scheme based on Pydantic was implemented. Each experiment plan generated by GPT-5 was formally checked to exclude invalid concentrations, inconsistent plate layouts, or infeasible parameter combinations. Only after successful validation was the experiment physically executed.[6][9]

The closed control loop thus consisted of four steps:

- Generation of an experimental design by GPT-5

- Formal validation of the design

- Robotic execution via Catalyst and RAC modules

- Return of measurement data to the model for optimization

This process was repeated over six iterations, with the model increasingly identifying narrower parameter regions that led to higher efficiency at lower cost.[1][3]

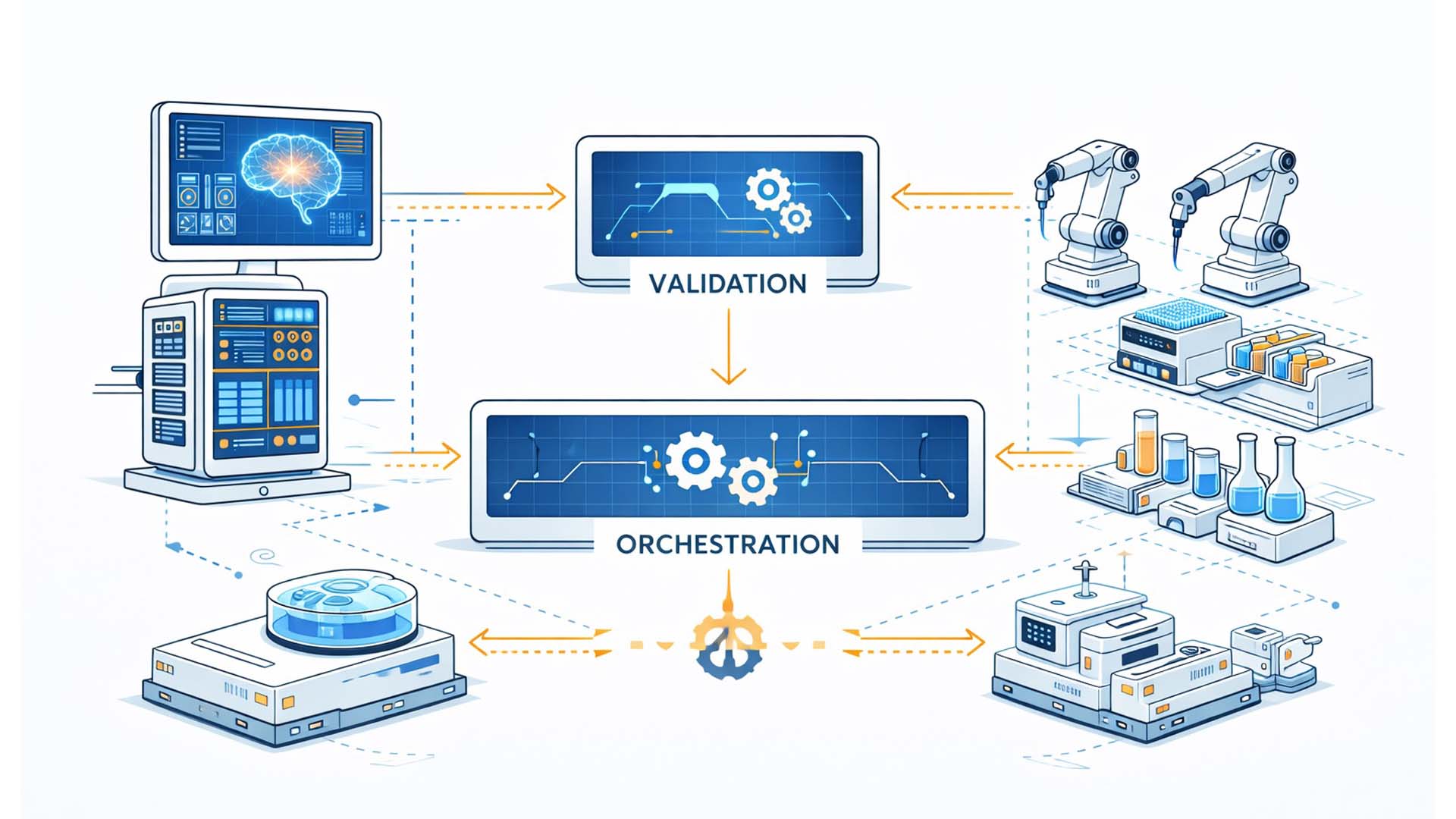

Closed-loop architecture: Language model, validation, robotics, and measurement systems in a continuous control cycle

Illustration: Editorial conceptual depiction of an autonomous AI laboratory system

The decisive difference compared to classical high-throughput laboratories lies not only in automation, but in decision integration. While conventional systems process predefined parameter sequences, the AI system evaluates results independently and dynamically adapts its strategy. The laboratory thus functionally behaves like a learning system.

The next chapter analyzes the technical architecture of this pipeline in detail.

Technical Architecture – AI, Validation, and Modular Robotics

The autonomous laboratory system is based on a multilayered architecture that connects cognitive AI decision processes with physical laboratory automation. At the center stands the language model GPT-5 as the strategic control instance. It handles hypothesis generation, parameter optimization, data analysis, and the planning of subsequent experiments.[2][5]

GPT-5 did not operate in isolation, but within a controlled agent environment with access to scientific literature, preprints, and a Python-based analysis environment. This enabled the model to incorporate external domain knowledge and independently perform statistical evaluations. According to published reports, the model interpolated standard curves, identified outliers, and analyzed parameter clusters before designing new experimental series.[6][10]

The interface between model and laboratory hardware was implemented via a structured JSON schema defined using Pydantic. This schema described each 384-well plate in machine-readable form, including reagents, concentrations, control samples, and volumes. The objective was to algorithmically prevent hallucinations or physically impossible combinations.[6][9]

Only validated designs were forwarded to the automation layer. At Ginkgo, this layer is realized through the software Catalyst, which functions as an orchestrator. Catalyst translates JSON-defined experiments into concrete control protocols for laboratory devices and coordinates workflows between pipetting robots, incubators, and measurement instruments.[4][8]

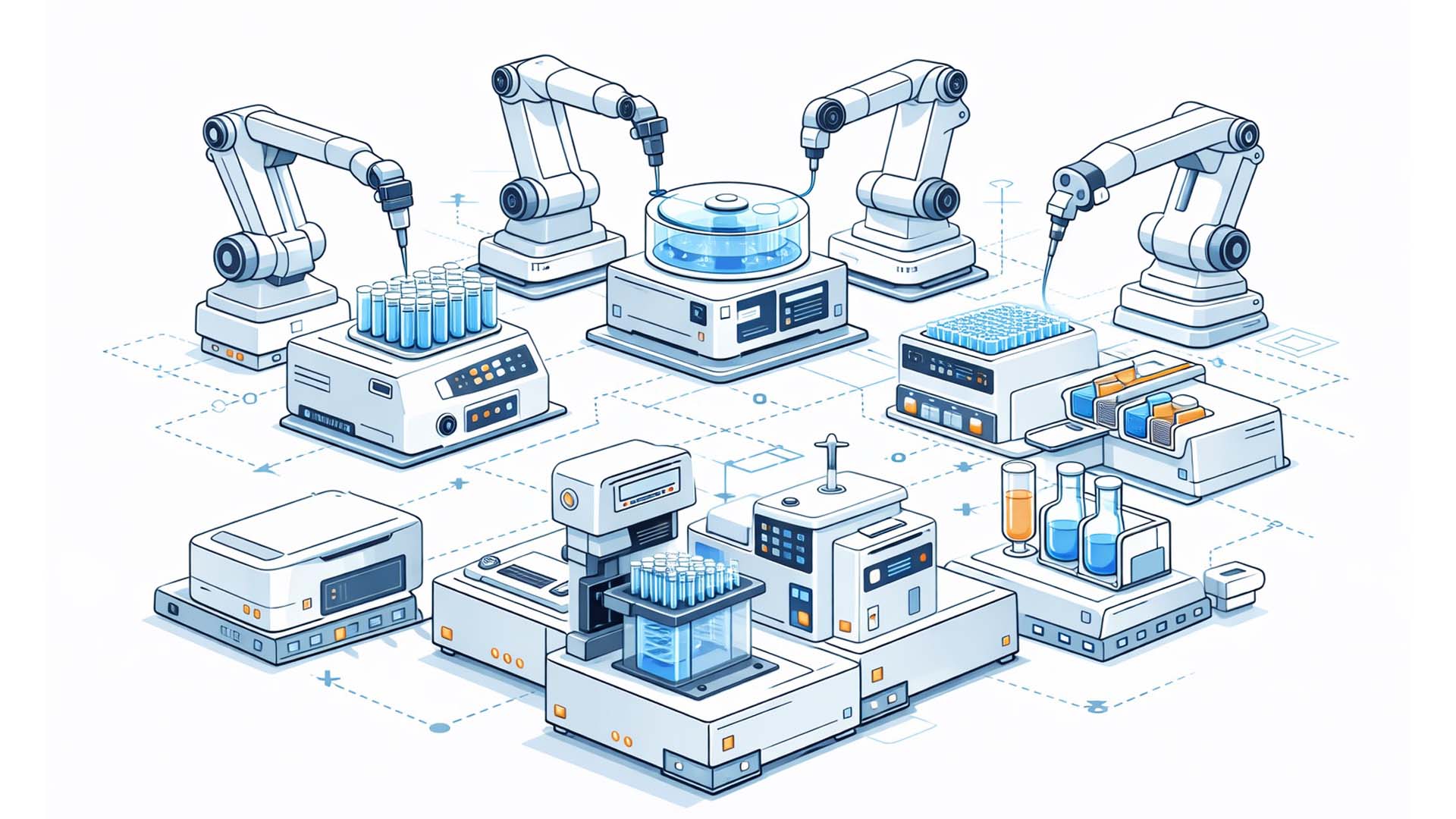

The physical layer consists of the so-called Reconfigurable Automation Carts. Each unit contains a robotic arm and a specific laboratory device. Multiple RACs can be modularly connected to create complex process chains. Microplates are automatically transported between modules without human intervention.[8]

Modular RAC architecture: Robotic arms and laboratory devices as combinable automation units

Illustration: Conceptual depiction of a modular laboratory automation platform

After completion of the incubation phase, reaction results were quantified using fluorescence or spectral measurement. These raw data, together with metadata such as incubation time, device status, and plate layout, were transmitted back to GPT-5. The model analyzed the results and derived the next iteration.[7][10]

Functionally, the architecture can be divided into the following layers:

- Cognitive layer → GPT-5 as hypothesis and optimization instance

- Validation layer → Pydantic schema ensuring laboratory-ready designs

- Orchestration layer → Catalyst as workflow coordinator

- Hardware layer → RAC modules for robotic execution

- Measurement and feedback layer → Sensors and data return

The structural added value of this architecture lies in the tight coupling of all layers. While classical laboratory automation executes predefined protocols, here a learning model decides which protocols are meaningful next. The physical infrastructure becomes the executing instance of a data-driven optimization logic.[2][4]

Particularly relevant is the decoupling of cognitive and physical layers. The model itself does not execute robotic code, but defines experimental parameters exclusively. Safety-critical implementation remains anchored within the controlled automation environment. This separation reduces the risk of uncontrolled system states and increases auditability.[9]

The next chapter examines specific implementation details as well as software and infrastructure considerations.

Implementation Details, Software Stack, Interfaces, and Safety Mechanisms

The demonstration of the autonomous laboratory depended not only on the performance of the language model, but on precisely tuned system integration. The technical core was a pipeline that brings together AI agent logic, structured validation, workflow orchestration, and physical laboratory automation within a controlled environment.[2][6]

On OpenAI’s side, GPT-5 was operated in an agent environment that enabled access to Python-based analysis tools, web research in scientific sources, and persistent data storage for measurement data. This allowed the model to combine literature context with numerical evaluation and, after each data delivery, immediately derive new experiment plans. In the described workflows, data cleaning, outlier detection, and model-based interpolation were used, among other methods, before new parameter regions were tested.[5][10]

The interaction between AI and laboratory took place via structured JSON definitions. Each experiment description encoded a complete 384-well plate layout with reagents, concentrations, volumes, controls, and dilutions. This form of machine-readable specification is decisive because it limits the model to the role of parameter decision making and anchors execution consistently within the automation environment.[6][9]

A central safety instrument was the Pydantic validation schema. It checked each AI-generated design for laboratory feasibility, such as permissible volume ranges, consistent controls, and rule-compliant combinations. Invalid or impractical suggestions were automatically rejected before they could reach the hardware. This addressed a critical risk pathway, namely the transfer of erroneous model proposals into real liquid handling workflows.[9]

After validation, the Catalyst software took over orchestration. Catalyst transformed the JSON protocols into concrete device operations, coordinated pipetting sequences, incubation steps, and measurement routines, and controlled plate transport between the modular RAC units. At the same time, the system captured protocol data and metadata for traceability and auditability.[4][8]

Implementation logic, structured interface between model, validation, orchestration, and modular laboratory hardware

Illustration: Editorial system depiction of the AI to laboratory pipeline

- Structured interface → Experiments are described as JSON, not as robotic code

- Formal validation → Pydantic filters impermissible designs before execution

- Orchestrated execution → Catalyst coordinates RAC modules, measurement, and data return

The temporal architecture is also important. Biological incubation phases take many hours, which means the system does not require hard real time at the millisecond level. What matters is a reliable asynchronous sequence: design, execution, measurement, return, next iteration. In this logic, research becomes faster not through reaction time, but through closed automation and fast decision iteration.[1][7]

From a safety perspective, human oversight remained part of operations, especially for reagent management, maintenance, and emergency shutdown. In addition, the model’s decisions were logged. GPT-5 produced explanatory notes that documented each optimization step and the underlying reasoning, supporting later audits and reproducibility.[9]

The next chapter places the scientific context and shows how this demonstration connects to self-driving lab research and what differences emerge from embedding a large language model.

Scientific Context, Self-Driving Labs, and the Role of Large Language Models

Autonomous laboratories are not an isolated event, but part of a growing research field discussed under terms such as self-driving labs or closed-loop experimentation. In chemistry, materials science, and biotechnology, robot-assisted platforms have been combined with machine learning for several years to solve optimization tasks in an automated manner.[11][12]

Typically, these systems are based on Bayesian optimization or other active learning methods. They generate new parameter combinations, carry out experiments automatically, and use the results to gradually narrow the search space. The focus is usually on clearly defined target variables such as yield, stability, or reaction speed.[11][13]

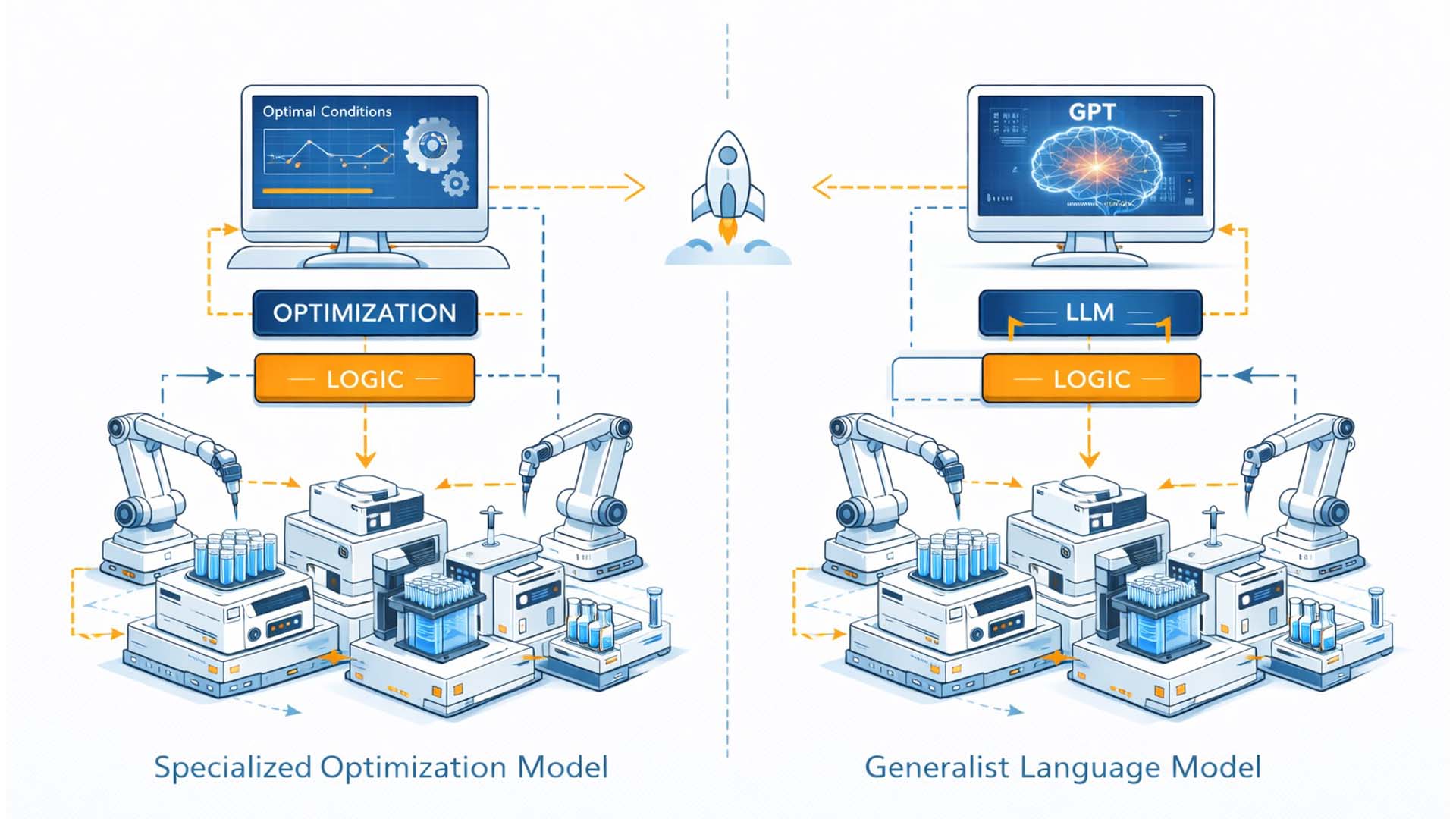

The OpenAI × Ginkgo demonstration extends this paradigm in two ways. First, it does not rely on a specialized optimization model, but on a large language model originally trained for text processing. Second, this model takes over not only parameter optimization, but also context integration, literature research, and experimental justification. This shifts the role of AI from a pure optimization tool to a general decision making instance.[2][5]

Earlier self-driving lab projects often operated at prototype level or within tightly constrained research settings. Here, by contrast, a scaled cloud laboratory infrastructure was used, in which more than 36,000 variants were executed in reality. The difference lies not only in scope, but in the depth of integration between model, validation, and physical robotics.[1][7]

From specialized optimization models to a general language model as the decision making instance in the autonomous laboratory

Illustration: Editorial comparison of classical SDL architecture and LLM-integrated laboratory control

- Classical SDL systems → Specialized optimization algorithms with clearly defined target metrics

- LLM-based systems → Context integration, literature access, and experimental justification

- Scaled infrastructure → Cloud laboratory with thousands of real executed variants

In the scientific discourse, it is increasingly debated how such platforms could democratize research. Cloud-based laboratories theoretically allow experiments to be defined remotely and executed automatically. Canty et al. describe in this context that digital protocols can be translated directly into physical laboratory operations, significantly accelerating the transfer from hypothesis to test.[12][14]

At the same time, language models raise new questions. While classical optimizers are constrained by mathematically defined objective functions, large language models operate probabilistically and context-sensitively. Their strength lies in generalization, their weakness potentially in the lack of formal guarantees. The integration of a validation schema such as Pydantic thus becomes not only a technical, but an epistemic necessity.[6][9]

Another difference concerns interpretability. In the demonstration, GPT-5 produced explanatory laboratory notes that documented its optimization strategy. This is scientifically relevant because it builds a bridge between a black box model and nachvollziehbarer experiment planning. It remains open, however, to what extent such justifications are truly causal or merely plausibly formulated.[9][11]

The next chapter analyzes concrete applications and economic implications of this technology, especially with regard to cost reduction, acceleration of research and development processes, and new business models.

Applications and Benefits, Accelerating Biological Research Through AI-Controlled Closed-Loop Systems

The economic and scientific relevance of the demonstration is most evident in the achieved efficiency gains. Within six iteration cycles, the specific production cost structure of cell-free protein synthesis was reduced by around 40 percent. The costs per gram of protein dropped from approximately 698 US dollars to roughly 422 US dollars.[1][3]

This reduction is not an isolated effect of individual parameter adjustments, but the result of systematic, data-driven exploration. The model did not test combinations at random, but learned iteratively which concentration ratios and reagent mixtures were particularly promising. As a result, the search space gradually condensed into economically optimal regions.[5][7]

For industrial applications, this means a fundamental shift in research logic. Classical laboratory optimization is highly sequential and labor intensive. Hypotheses are formulated, tested, manually evaluated, and then adjusted. A closed-loop system, by contrast, can operate automatically day and night, significantly shortening the time to identify optimal parameters.[11][12]

The following fields of application are particularly relevant:

Application spectrum, from protein optimization to drug discovery and materials research

Illustration: Editorial visualization of possible application areas for autonomous laboratory systems

- Biopharma development → Optimization of expression systems, formulations, and production conditions

- Enzyme engineering → Systematic search for more stable or more efficient variants

- Materials and catalyst research → Automated exploration of complex parameter landscapes

In drug development, thousands of experimental variants could be automatically tested to optimize stable protein structures, antibodies, or vaccine components. A similar pattern applies in materials research, where compositions of catalysts or battery materials can be tested against defined performance metrics.[11][13]

Another benefit lies in the scaling of knowledge. Because the language model incorporates literature and combines experimental results with external findings, a hybrid form of knowledge processing emerges. Research becomes not only faster, but potentially more broadly contextualized. The system can, for example, consider current preprints and immediately test experimentally whether the described parameter ranges are reproducible.[5][6]

Economically, new business models open up. AI-optimized reagents or production mixtures can be marketed directly. Combined offerings of AI agents and cloud laboratory infrastructure are also conceivable, where companies outsource optimization tasks without having to invest themselves in full robotics.[1]

In the long term, the cost structure of research and development shifts. Instead of investing large budgets in manual iterations, a significant share of optimization work can be automated. This yields more experimental evidence per invested dollar and significantly shortens development cycles.

The next chapter analyzes the associated risks, safety issues, and governance challenges.

Risks and Governance, Biosecurity, Failure Risks, and Regulatory Requirements

As promising as autonomous AI-controlled laboratories are, the associated risks are equally complex. Integrating a large language model into a physical experimental loop shifts layers of responsibility and opens new attack surfaces. In addition to technical failure risks, questions of biosecurity, cybersecurity, and regulatory classification move into focus.[15][16]

A central topic is biosecurity. In the demonstration, cell-free protein synthesis was used, meaning without living organisms. Still, the principle shows that AI systems could potentially also control more complex biological processes. Without appropriate control mechanisms, there would be a risk of producing dangerous combinations of reagents or genetic material. Therefore, a strict limitation of the accessible reagent catalog and multi-stage validation are essential.[15][17]

Another risk concerns the reliability of the language model itself. Large language models operate probabilistically and can generate faulty or not fully consistent proposals. The validation schema described in chapter three significantly reduces this risk, but it does not replace comprehensive system oversight. Especially at scale, it must be ensured that systematic misinterpretations are detected early.[6][9]

Cybersecurity is an additional dimension. Because the model interacts with literature sources and digital interfaces, there is a theoretical risk of manipulation through external data sources or targeted inputs. Isolated infrastructure, access controls, and detailed logging are therefore central elements of responsible system design.[16]

Multi-layer governance structure, technical validation, human oversight, and regulatory framework

Illustration: Editorial depiction of safety and governance layers in autonomous laboratory systems

- Biosecurity control → Limited reagent catalogs and formal validation of all designs

- Model oversight → Logging, auditability, and human review instances

- Cybersecurity → Isolated networks, access restrictions, and manipulation protection

Regulatorily, autonomous laboratories operate at the intersection of biotechnology, medical law, and AI regulation. In the European Union, such a system would likely fall under high-risk AI if used in safety-critical or medical contexts. At the same time, existing biosecurity and genetic engineering regulations apply, which have so far been primarily oriented toward human operators.[16][18]

Another governance issue is liability. If an AI system makes experimental decisions, the question arises of responsibility in case of faulty results or damages. Is the laboratory operator responsible, the AI provider, or the developer of the validation interface. These questions are only partially clarified legally and require new regulatory guidelines.[15]

A positive aspect is the auditability implemented in the demonstration. GPT-5 documented its decision logic in explanatory notes. In addition, validation code and parts of the infrastructure were made openly accessible. This transparency is an important step toward building trust in autonomous systems.[9]

In the long term, it will be crucial to understand governance not as downstream regulation, but as an integral part of the architecture. Only if safety mechanisms, human oversight, and technical limitations are embedded from the start can autonomous laboratories be socially accepted and scaled in industry.

The next chapter analyzes the economic and organizational impacts of this technology.

Economic and Organizational Impacts, New Business Models, and Changing Role Profiles

The introduction of autonomous AI-controlled laboratories is not only technologically disruptive, but also changes economic and organizational structures in research and industry. When a language model like GPT-5 generates experimental designs, optimizes costs, and learns iteratively, the focus shifts from manual execution to strategic control and data interpretation.[9][14]

A central economic argument is increased efficiency. In the demonstration, cell-free protein synthesis could be made around 40 percent more cost-effective.[9] This saving does not arise solely from cheaper raw materials, but from targeted parameter optimization, fewer failed attempts, and accelerated learning cycles. In classical laboratory environments, comparable optimizations would take months or years. An autonomous system, by contrast, can run experimental series around the clock and immediately recalibrate based on real data.

This creates new business models. Cloud-based laboratory services, AI-optimized reagents, or modular automation platforms could establish themselves as independent market segments. Companies that possess both AI capabilities and automated infrastructure gain strategic advantages. At the same time, smaller research teams can access powerful laboratory resources via external platforms without having to operate high-tech infrastructure themselves.[12][14]

Organizationally, role distribution changes. Routine tasks such as pipetting or manual screening move into the background. Instead, skills in data analysis, automation architecture, and AI control gain importance. Researchers define hypotheses and target metrics, while AI systems explore large parameter landscapes. Technicians monitor infrastructure, interfaces, and safety mechanisms.[13][14]

Transformation of laboratory work, from manual execution to data-driven system control

Illustration: Editorial visualization of organizational changes through autonomous AI laboratory systems

- Cost reduction → Fewer failed attempts and accelerated optimization cycles

- New business models → AI-optimized reagents and lab as a service platforms

- Role shift → More data competence, less manual routine work

Innovation dynamics also change. When closed-loop systems learn continuously, the number of possible experiments increases drastically. Research becomes more iterative, more data intensive, and more model based. Decisions rely less on isolated single experiments and more on systematic exploration strategies. This can significantly reduce time to market in areas such as biopharma, materials development, or enzyme design.[14]

At the same time, investment requirements emerge. Building autonomous laboratory platforms requires substantial upfront costs for robotics, software integration, and AI infrastructure. In the long term, however, economies of scale could arise, where large experiment volumes lead to decreasing costs per insight.

Economically, autonomous laboratories therefore mark not only an efficiency gain, but a structural change in knowledge production. Research is increasingly understood as an orchestrated data process in which AI, robotics, and human expertise are tightly interlinked.

In the following chapter, scaling questions and long-term implementation hurdles are analyzed.

Video, Closed Loop AI Laboratory in Real Operation

On February 11, OpenAI released the demonstration “GPT-5 × Ginkgo Bioworks Autonomous Laboratory.” The video provides the first visible documentation of a fully integrated closed loop laboratory architecture in which a large language model designs real experiments, has them executed robotically, and optimizes them further based on measurement data. The following classification is provided from an analytical perspective by Ulrich Buckenlei.

The video reveals a structural shift. Artificial intelligence is no longer an analytical tool at the periphery of the system, but part of the operational infrastructure. The model generates experimental designs, the automated laboratory platform implements them physically, the results flow back, and form the basis for the next iteration. Decision logic, execution, and optimization are connected within a continuous control loop.

The economic dimension is particularly relevant. The demonstrated architecture reduced protein production costs by around 40 percent. This is not incremental progress, but a structural productivity leap. Autonomous laboratory systems therefore appear as the first visible manifestation of an AI native industrial infrastructure.

GPT-5 controlled closed loop experiment architecture in the Ginkgo Autonomous Lab

Video source: OpenAI | GPT-5 × Ginkgo Bioworks Autonomous Laboratory Demonstration | Analysis: Ulrich Buckenlei

With this demonstration, the transition from assistance system to infrastructural AI becomes visible. Research is not only supported, but structurally reorganized.

Sources and References

- OpenAI, “Introducing GPT-5 for Scientific Discovery and Autonomous Labs”, blog post on the closed-loop demonstration with Ginkgo Bioworks, 2026. [1]

- Ginkgo Bioworks, press release on the cooperation with OpenAI and the 40 percent cost reduction in cell-free protein synthesis, 2026. [9]

- BioRxiv Preprint, technical report on the autonomous optimization of CFPS reactions by GPT-5 in a closed feedback loop, 2026. [3]

- Nature Communications, Canty et al., “Self-Driving Laboratories and Cloud-Integrated Experimentation Platforms”, 2025. [14]

- Royal Society Open Science, Tobias & Wahab, “Self-Driving Labs: Governance, Patent and Biosecurity Considerations”, 2025. [13]

- Pydantic Documentation, validation of structured data schemas for machine-readable laboratory protocols, Python Foundation. [6]

- Ginkgo Bioworks Catalyst Platform, technical description of the orchestration software for modular laboratory automation, 2025. [19]

- SLAS Technology, publications on Reconfigurable Automation Carts (RAC) and modular laboratory robotics, 2024–2026. [32]

- OpenAI × Ginkgo Demonstration Data Release, summary of iterations, 36,000 experimental variants, and cost reduction metrics. [9]

- US Department of Energy, Genesis Mission, integration of supercomputing, AI, and autonomous laboratories, 2025. [12]

- Council on Strategic Risks, recommendations on biosecurity and AI-enabled biotechnology, 2025. [15]

- European Union AI Act, regulatory framework for high-risk AI systems in safety-critical applications, 2024. [16]

- ENISA, guidelines on cybersecurity in AI-enabled industrial systems, 2024. [17]

- Gend.co, analysis of closed-loop laboratory platforms and AI-optimized research, 2026. [22]

- Open Source Release – Validation Schema, release of the experimental JSON validation schema by Ginkgo Bioworks, GitHub repository, 2026. [38]

- European Biosafety Framework, guidelines on genetic safety and laboratory operations in the EU, 2023–2025. [18]

When Autonomous Laboratories Become a Strategic Decision Question

The collaboration between OpenAI and Ginkgo Bioworks shows that autonomous AI-controlled laboratories are no longer a futuristic concept, but a technology implemented in reality with measurable economic impact. What is decisive is not only the language model used or the robotics platform, but the underlying system paradigm. Research is no longer planned and conducted exclusively manually, but organized as a data-driven, closed optimization cycle.

For decision makers, this shifts the basis of evaluation. Less relevant is the question of individual laboratory devices or isolated AI functions. The focus is on architecture, validation, governance, and integrability into existing processes. Anyone who wants to deploy autonomous laboratories must consider system stability, auditability, and regulatory compliance just as much as efficiency gains and cost reduction.

Whether in drug discovery, enzyme design, materials research, or process optimization, AI-controlled closed-loop systems open up new options for action. At the same time, requirements for safety mechanisms, ethical control, and organizational adaptability increase. The central question is therefore not whether autonomous laboratories will come, but under which conditions they can be deployed responsibly and at scale.

The Visoric Expert Team: Ulrich Buckenlei and Nataliya Daniltseva in discussion about autonomous systems, industrial AI, and data-driven research architectures

Source: VISORIC GmbH | Munich

At this intersection of technology, regulation, and strategic decision making, the Visoric expert team in Munich is active. The focus is on analytical classification of complex AI and automation systems, evaluation of opportunities and risks, and the clear communication of technological developments for management, investors, and public institutions.

- Strategic assessment of autonomous laboratory systems and AI research architectures

- Analysis of safety, governance, and regulatory frameworks

- Translation of complex AI and automation processes for decision makers

- Concept design for visualizations, scenarios, and technology-assisted decision models

If you would like to assess what role autonomous AI-controlled laboratories can play in your innovation strategy, an exchange with the Visoric expert team offers a well-founded, independent, and practice-oriented perspective.

Contact Persons:

Ulrich Buckenlei (Creative Director)

Mobile: +49 152 53532871

Email: ulrich.buckenlei@visoric.com

Nataliya Daniltseva (Project Manager)

Mobile: +49 176 72805705

Email: nataliya.daniltseva@visoric.com

Address:

VISORIC GmbH

Bayerstraße 13

D-80335 Munich